The Unseen Foundation: Why Soil is a Critical Natural Resource and Environmental Linchpin

Far from being inert dirt, soil is a dynamic, living ecosystem, a conditionally renewable natural resource that serves as the foundational nexus for Earth’s terrestrial life, climate, and hydrological cycles. [1] Its profound importance extends far beyond agriculture, anchoring the stability of our environment and the resilience of human civilization. The complex interplay of its physical, chemical, and biological properties provides a suite of indispensable ecosystem services that are often undervalued and are now under significant threat. A deeper examination reveals that the health of this subterranean world is inextricably linked to global economic stability, human well-being, and the fight against climate change, making its preservation a paramount concern.

The Engine of Sustenance and a Reservoir of Health

The most recognized function of soil is underpinning global food production by providing a medium for plant growth, but its role is far more intricate than simply holding roots. [2] Healthy soils are complex biogeochemical engines that actively manage and supply the essential nutrients vital for plant life. [2][3] This process is governed by properties like cation exchange capacity and a vibrant microbial community that transforms elements into forms accessible to plants. For instance, soil microorganisms like bacteria and fungi are responsible for decomposing organic matter and cycling crucial nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. [4] Some bacteria perform nitrogen fixation, converting atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form for plants—a natural process that industrial fertilizers replicate at a high energy cost. [3] This microbial activity directly impacts human health; nutrient-rich soils produce more nutritious crops, while depleted soils can lead to food with lower vitamin and mineral content, contributing to malnutrition. Beyond nutrition, soil is a critical source for medicine. A vast and largely untapped reservoir of genetic material exists within soil’s microbial biodiversity, which has already yielded revolutionary medical treatments. [5][6] A prime example is the discovery of streptomycin, an antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis, which was isolated from the soil bacterium Streptomyces griseus. [6] This highlights soil not just as a medium for sustenance, but as a frontier for scientific discovery with direct benefits to human health. [4]

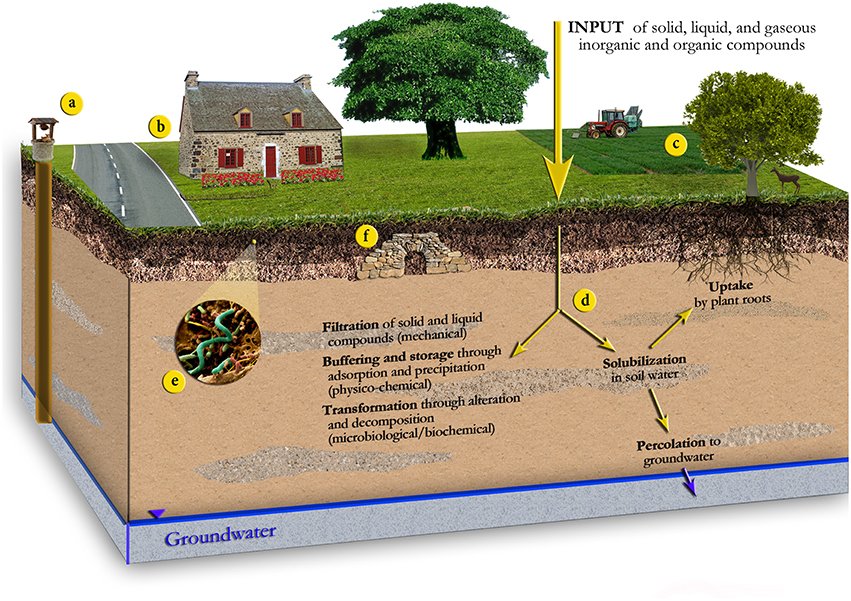

The Planet’s Living Filter and Hydrological Regulator

Soil performs a vital, life-sustaining function as the planet’s largest natural water filter and storage system. [7][8] As rainwater and surface water percolate downward, the soil matrix acts as a sophisticated, multi-stage filtration system. [9] Physically, particles like sand and silt trap suspended solids. Chemically, clay particles and organic matter, with their electrically charged surfaces, adsorb and immobilize a host of pollutants, including heavy metals and excess agricultural nutrients like nitrates and phosphates that could otherwise contaminate groundwater. [2][10] Biologically, a diverse community of soil microbes actively degrades organic pollutants, pesticides, and pathogens, transforming them into less harmful substances. [11] Beyond purification, soil’s capacity to absorb and retain water is fundamental to environmental stability. Healthy soils, rich in organic matter, can store vast quantities of water, which is crucial for mitigating the impacts of both floods and droughts. [8][12] By absorbing excess rainfall, healthy soil reduces surface runoff, lessening the severity of floods and preventing soil erosion. [13][14] During dry periods, this stored water becomes a critical reservoir for plant growth, enhancing ecosystem resilience and ensuring agricultural productivity. [12] This hydrological regulation directly protects human communities and infrastructure from the increasing frequency of extreme weather events. [13]

A Decisive Force in Climate Regulation and Global Stability

Soil is a powerhouse in the global carbon cycle and a critical, yet vulnerable, component of climate regulation. [15][16] After the oceans, soil is the planet’s second-largest carbon sink, storing approximately three times more carbon than all terrestrial vegetation and twice as much as the atmosphere. [5][17] This carbon is stored primarily in the form of soil organic matter (SOM), which is created from decomposed plant and animal residues. [18] Through photosynthesis, plants capture atmospheric CO2, and this carbon is transferred to the soil, where stable forms like humus can sequester it for centuries. [16][18] This natural process makes healthy soil a potent tool for climate change mitigation, with the potential to sequester over a billion additional tons of carbon each year through improved management practices like conservation tillage and the use of cover crops. [19] However, this function is a double-edged sword. Degradative practices such as intensive farming, deforestation, and urbanization expose soil organic matter to oxygen, accelerating its decomposition and releasing massive quantities of stored carbon back into the atmosphere as CO2, turning a vital sink into a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions. [19] Furthermore, soil management influences other powerful greenhouse gases, notably nitrous oxide, whose emissions can be exacerbated by the inefficient use of nitrogen fertilizers. [4][16]

The economic and social ramifications of failing to protect this resource are severe. Soil degradation directly undermines agricultural productivity, leading to reduced income for farmers, higher food prices for consumers, and threats to global food security. [20][21] These impacts ripple through interconnected sectors, from food processing to retail, and can damage critical infrastructure through erosion and sedimentation. [20] On a societal level, the loss of productive land can trigger migration, social unrest, and the loss of cultural heritage, demonstrating that soil health is a cornerstone of economic and social stability. [20][22] Therefore, recognizing soil as a multifunctional, conditionally renewable resource is essential for developing sustainable solutions to the world’s most pressing environmental and social challenges. [1]