Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory profoundly reshaped the understanding of the human psyche, introducing a dynamic model of personality structured around the concepts of the unconscious, the Id, the Ego, and the Superego. These theoretical constructs, while not physical entities, provide a compelling framework for analyzing the complex interplay of forces that drive human thought, emotion, and behavior. Freud posited that much of our mental life operates beyond conscious awareness, with these three psychic agencies constantly interacting, often in conflict, to shape an individual’s unique personality and their engagement with the world. This intricate model offers a profound glimpse into the hidden mechanisms that govern our actions and reactions, laying a foundational stone for modern psychology.

The Unconscious

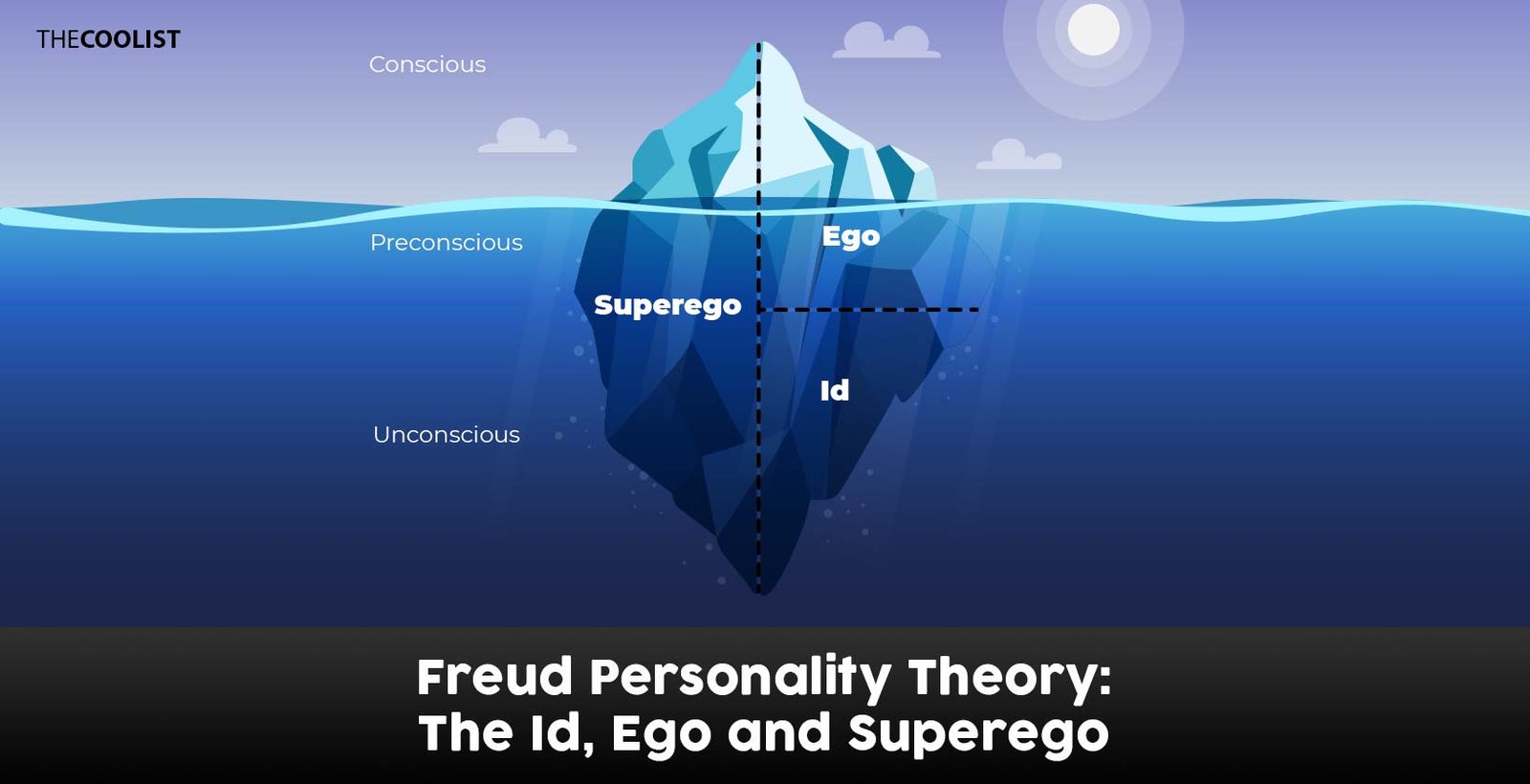

At the core of Freud’s topographical model of the mind lies the unconscious, a vast and enigmatic reservoir of feelings, thoughts, urges, and memories that remain inaccessible to conscious awareness. Freud famously likened the mind to an iceberg, with the conscious mind being merely the visible tip, and the immense, submerged portion representing the unconscious, which he believed to be the primary source of human behavior [1][2]. This hidden realm contains deeply rooted desires, repressed memories, and traumatic experiences that, despite being out of sight, exert a powerful and continuous influence on our conscious thoughts, motivations, and decisions [2][3].

The unconscious operates on what Freud termed “primary process thinking,” characterized by irrationality, emotionality, and a complete disregard for logic, reality, or time [1][4]. It allows contradictory ideas to coexist and seeks immediate gratification of primitive urges, often through symbolic representations [1][5]. For instance, distressing thoughts or impulses deemed too threatening to acknowledge are often repressed into the unconscious, yet they can manifest in disguised forms such as dreams, slips of the tongue (Freudian slips), or even neurotic symptoms [1][2]. Freud considered dreams “the royal road to the unconscious,” believing they reveal hidden wishes and conflicts through their latent content [2][3]. A classic example of an unconscious influence is a “Freudian slip,” where an unintentional error in speech or memory reveals an underlying, unacknowledged thought or desire, such as a politician “accidentally” referring to a colleague as “the honorable member from Hell” instead of “Hull” [1]. The ultimate goal of psychoanalysis is to bring these unconscious materials into conscious awareness, thereby resolving internal conflicts and alleviating psychological distress [1][6].

The Id

The Id represents the most primitive and entirely unconscious component of the personality, present from birth [6][7]. It is the source of all basic biological needs, instincts, and desires, functioning as a “cauldron of seething excitations” [4][8]. Operating solely on the “pleasure principle,” the Id relentlessly seeks immediate gratification of its urges, without any consideration for reality, logic, morality, or consequences [6][7]. This includes fundamental drives such as hunger, thirst, sexual desire (libido), and aggression [7][9]. Freud categorized these instinctual drives into two main categories: Eros, the life instinct, which encompasses self-preservation and sexual drives, and Thanatos, the death instinct, associated with aggression and destructive impulses [1][4].

The Id is impulsive, chaotic, and lacks any organization or collective will; its sole concern is the reduction of tension that arises when its needs are unmet [6][9]. An infant crying incessantly until fed or comforted perfectly illustrates the Id in action, driven purely by the immediate need for satisfaction [8][10]. Similarly, if a person is hungry, the Id compels them to eat immediately, disregarding whether it’s an appropriate time or place [7][10]. The Id’s influence can also be seen in impulsive behaviors like overeating or excessive spending, where the immediate pleasure overrides any long-term considerations [10]. It is the raw, untamed aspect of the psyche, demanding instant fulfillment of its desires, and remaining unaffected by external reality throughout a person’s life [4][11].

The Ego

Emerging from the Id, the Ego develops as the rational and reality-oriented component of the personality [6][11]. Its primary function is to mediate between the instinctual demands of the Id, the moralistic constraints of the Superego, and the practicalities of the external world [4][6]. Unlike the Id, the Ego operates on the “reality principle,” striving to satisfy the Id’s desires in ways that are realistic, socially appropriate, and avoid negative consequences [4][6]. This often involves delaying gratification, finding compromises, or seeking alternative, acceptable means of fulfillment [4][6].

The Ego functions across all three levels of consciousness—conscious, preconscious, and unconscious—though it is the only part of the personality that is largely conscious and what an individual perceives as their “self” [4][11]. It employs various “secondary process thinking” functions, including judgment, problem-solving, reality testing, control, planning, and memory [6][11]. For example, if the Id demands an entire cake, the Ego, guided by the reality principle, considers the consequences (e.g., stomach ache, social disapproval) and might decide to eat only a small portion or wait for a more suitable time [12]. The Ego is not concerned with right or wrong in a moral sense, but rather with what is practical and effective in maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain within the bounds of reality [11]. To manage the inevitable conflicts and anxieties arising from the Id’s demands and the Superego’s strictures, the Ego also employs defense mechanisms (e.g., repression, denial), which are unconscious strategies that distort reality to protect the individual from distress [1][6].

The Superego

The Superego is the last component of personality to develop, typically emerging around the age of five or six, through the internalization of moral standards and ideals from parents, societal norms, and cultural values [6][7]. It serves as the individual’s moral compass, striving for perfection and acting as a conscience that guides behavior towards ethical standards [7][12]. The Superego has two main components: the conscience and the ego ideal [7][13]. The conscience incorporates information about what is considered “bad” or forbidden by authority figures and society, leading to feelings of guilt, shame, or remorse when these internalized rules are violated [7][13]. The ego ideal, conversely, represents the rules and standards for “good” or ideal behaviors that the Ego strives to achieve, rewarding the individual with feelings of pride and self-esteem when these moral standards are met [7][13].

The Superego operates on the “morality principle,” working to suppress the Id’s urges that are deemed wrong or socially unacceptable, and compelling the Ego to act morally rather than realistically [4][12]. For instance, if the Id urges someone to cheat on a test for immediate success, the Superego intervenes, reminding them of the value of honesty and integrity, and inducing guilt if the temptation is considered [6][12]. An overly dominant Superego can lead to excessive guilt, self-criticism, and perfectionism, even for minor transgressions or mere thoughts [4][13]. Conversely, a weak Superego might result in a lack of moral restraint. Like the Ego, the Superego operates across conscious, preconscious, and unconscious levels, meaning individuals can experience guilt without fully understanding its unconscious origins [13].

Dynamic Interplay

Freud’s genius lies not in the isolated definition of these components, but in their constant, dynamic, and often conflicting interaction, which ultimately shapes an individual’s personality and behavior [6][14]. The Id relentlessly pushes for immediate gratification, driven by primal instincts. The Superego, on the other hand, imposes moralistic restrictions and strives for an ideal, often opposing the Id’s raw demands. Caught in the middle, the Ego acts as the crucial mediator, attempting to find a realistic and socially acceptable balance between these powerful, often opposing, forces and the constraints of the external world [6][14].

This ongoing negotiation is fundamental to psychological stability. A healthy personality is characterized by an Ego strong enough to effectively manage these internal conflicts, ensuring that instinctual desires are met in ways that align with societal norms and moral principles [4][12]. When the Ego struggles to maintain this balance, psychological distress, anxiety, or maladaptive behaviors can arise [6][15]. For example, a person on a diet might experience the Id’s craving for a forbidden dessert, the Superego’s guilt over breaking the diet, and the Ego’s attempt to compromise by allowing a small, controlled portion [4]. The constant tension and resolution between the Id, Ego, and Superego are central to Freud’s understanding of human experience, providing a framework for comprehending the complexities of inner conflict and the development of psychological well-being.

Conclusion

Sigmund Freud’s structural model of the psyche, comprising the unconscious, the Id, the Ego, and the Superego, remains a cornerstone of psychoanalytic theory and has profoundly influenced the field of psychology. While subject to criticism, particularly regarding its scientific testability and empirical evidence, the model offers an enduringly insightful framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of human personality and the origins of psychological conflict. By highlighting the profound impact of unconscious processes and the internal struggle between primal urges, rational thought, and moral imperatives, Freud provided a revolutionary lens through which to examine the human condition. His concepts continue to inform therapeutic practices, shape our understanding of motivation, and provide a rich vocabulary for discussing the complexities of the mind, solidifying his legacy as a pivotal figure in the exploration of human behavior.