The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Foundational Narrative of Human Consciousness

The Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known literary work in human history, stands as a monumental testament to the dawn of civilization and the timeless complexities of the human condition. [1][2] Originating from ancient Mesopotamia over four millennia ago, this epic poem transcends its archaeological significance, offering profound insights into the universal search for meaning, the nature of friendship, and the terrifying finality of death. [1][2] Its narrative, which evolved from disparate Sumerian poems into a cohesive Akkadian masterpiece, chronicles the transformative journey of a tyrannical king who ultimately confronts his own humanity. [3][4] The story’s rediscovery in the 19th century from the ruins of an ancient library unlocked a foundational text of world literature, revealing a sophisticated and deeply moving exploration of life and mortality that predates Homer by some 1,500 years. [3][5]

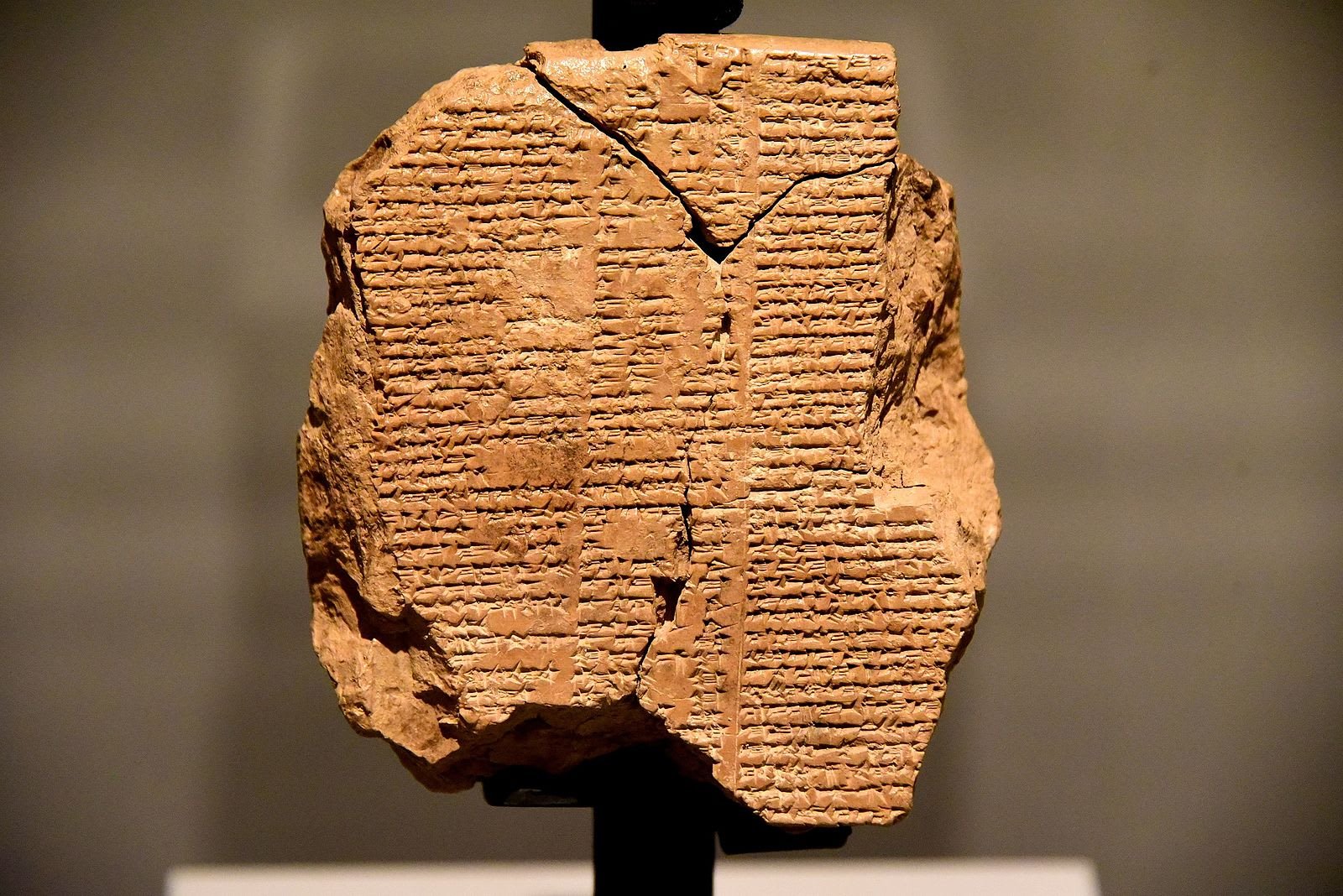

The epic’s origins are rooted in a historical figure, Gilgamesh, who reigned as the fifth king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk around 2700-2500 BCE. [5][6] Inscriptions credit him with constructing the great walls of Uruk, a feat mentioned within the epic itself. [5] Over time, the deeds of this historical king were embellished, culminating in five independent Sumerian poems that depicted him as a semi-divine hero. [3][6] These tales, likely dating to the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2100 BCE), were later synthesized and translated by Babylonian scribes. [3][7] The most significant literary evolution occurred with the creation of the “Old Babylonian” version around the 18th century BCE, which wove the separate stories into a single narrative titled Shūtur eli sharrī (“Surpassing All Other Kings”). [3] The most complete and refined version, however, is the “Standard Babylonian” text, compiled by a scholar-priest named Sîn-lēqi-unninni between 1300 and 1000 BCE. [3][8] It was this twelve-tablet version, titled Sha naqba īmuru (“He who Saw the Deep”), that was discovered in the 1850s among the ruins of King Ashurbanipal’s library in Nineveh, reintroducing the forgotten hero to the modern world. [3][9]

The narrative power of Gilgamesh lies in its profound psychological and philosophical journey, centered on the dynamic relationship between the titular hero and the wild man, Enkidu. Initially, Gilgamesh is a despotic ruler, two-thirds god and one-third human, whose arrogance oppresses the people of Uruk. [10][11] In response to their pleas, the gods create Enkidu, a being of nature, as a rival and counterpart to the king. [12] Enkidu’s transition from the wilderness, facilitated by an encounter with the temple prostitute Shamhat, symbolizes the complex process of civilization, where innocence is lost but wisdom and companionship are gained. [13][14] When Enkidu challenges Gilgamesh in Uruk, their titanic struggle transforms into a deep, loyal friendship that humanizes the tyrannical king. [12][15] This bond becomes the catalyst for Gilgamesh’s transformation; together they seek renown by journeying to the Cedar Forest to slay its monstrous guardian, Humbaba. [16] Their subsequent defiance of the goddess Ishtar by killing the Bull of Heaven leads the gods to decree Enkidu’s death, a punishment that marks the epic’s pivotal moment. [3] Enkidu’s demise shatters Gilgamesh, forcing him to confront the terror of his own mortality and launching him on a desperate quest for eternal life. [17] This quest is not merely for physical survival but is a search for meaning in a world defined by loss. [5]

The second half of the epic details Gilgamesh’s harrowing journey to the ends of the earth to find Utnapishtim, the only mortal granted immortality after surviving a great flood. [18] The account of the deluge, which Utnapishtim recounts on Tablet XI, bears striking parallels to the biblical story of Noah, including the divine warning, the construction of a vessel to save family and animals, and the use of birds to find dry land. [19][20] This narrative intersection is widely considered evidence of the Mesopotamian story’s influence on the Genesis account, given the earlier dating of the Gilgamesh texts. [21] Utnapishtim ultimately teaches Gilgamesh the futility of his quest, explaining that death is the destiny allotted to mortals by the gods. [17][18] After failing a test to conquer sleep, Gilgamesh is told of a plant that restores youth, which he obtains only to have it stolen by a serpent. [22] Defeated, he returns to Uruk, but his perspective is irrevocably altered. He finds solace not in eternal life, but in the enduring legacy of his works—the great walls of his city—and the wisdom gained through suffering. [17][23] This final realization elevates the epic from a heroic adventure to a profound meditation on accepting human limitations and finding immortality through cultural contributions. [23]

The enduring legacy of the Epic of Gilgamesh is a testament to its sophisticated exploration of themes that remain central to the human experience. [1] Its influence is a cornerstone of world literature, forming a prototype for the heroic saga and resonating in later works like the Homeric epics and the Hebrew Bible. [3][19] The poem provides an unparalleled window into the Mesopotamian worldview, where life was precarious and the gods were powerful yet capricious figures who controlled human destiny. [24][25] The central conflict between civilization and nature, embodied by Gilgamesh and Enkidu, explores the benefits and costs of societal living—the loss of primal innocence for the sake of community, knowledge, and order. [13][22] Ultimately, the epic’s most powerful message is its conclusion about mortality. It posits that while death is inescapable, a meaningful life can be achieved through friendship, wisdom, and the creation of a lasting legacy that benefits future generations. [2][17] In this way, Gilgamesh’s journey from a feared tyrant to a wise king who records his story for posterity ensures his immortality, not by escaping death, but by embracing the full, transient, and meaningful scope of human life. [5]