The Enduring Legacy: The Distortion of Previous Books and the Preservation of the Quran

Divine revelation, a cornerstone of monotheistic faiths, posits a direct communication from the Creator to humanity, guiding individuals and societies towards righteousness. Across Abrahamic traditions, a lineage of prophets is believed to have conveyed God’s messages, culminating in sacred texts intended to preserve these divine injunctions. Islam, as the final revelation, acknowledges the divine origin of earlier scriptures such as the Torah (Tawrat) revealed to Moses and the Gospels (Injil) revealed to Jesus. However, a central tenet within Islamic theology asserts that, over time, these preceding revelations underwent various forms of distortion, rendering their original, pristine messages incomplete or altered. This concept, known as “tahrif” in Arabic, stands in stark contrast to the unparalleled and meticulously documented preservation of the Quran, which Muslims believe remains precisely as it was revealed to Prophet Muhammad. This essay will delve into the Islamic understanding of the distortion of previous scriptures, explore the historical and theological mechanisms attributed to such alterations, and meticulously detail the unique and rigorous methods employed in the preservation of the Quran, underscoring its distinct status as a divinely safeguarded text.

The Concept of Previous Scriptures and their Alleged Distortion

The Islamic worldview embraces a continuous chain of divine guidance, recognizing prophets like Abraham, Moses, David, and Jesus as messengers who conveyed God’s word. Their respective scriptures—the Tawrat, Zabur (Psalms), and Injil—are revered as originally divine revelations. However, the Quran and subsequent Islamic scholarship introduce the concept of tahrif, or distortion, regarding these earlier texts. This distortion is understood in two primary forms: tahrif al-lafz (textual alteration) and tahrif al-mana (interpretational distortion). While some early Muslim scholars, such as al-Qasim al-Rassi and even al-Tabari, leaned towards tahrif al-mana, suggesting misinterpretation rather than outright textual change, later figures like Ibn Hazm strongly advocated for textual corruption. [1][2] Quranic verses themselves are interpreted by many to allude to such alterations, speaking of those who “write the Book with their hands and then say, ‘This is from Allah,’ so that they may gain thereby a trifling price,” or those who “twist their tongues while (reading) the Book, so that you may deem it to be from the Book, while it is not from the Book.” [3]

From an Islamic perspective, the human element in the transmission and compilation of these scriptures allowed for changes, whether intentional or unintentional. Historical and textual criticism of the Bible, while distinct from Islamic theological claims, does acknowledge the complex textual history of the Old and New Testaments. Scholars note the existence of numerous textual variants across biblical manuscripts, suggesting an evolution of the text over centuries through copying, translation, and redaction. [4][5] The absence of original autographs (the very first written copies) for biblical texts, coupled with the sheer volume of manuscript differences, contributes to this understanding. [5] While many of these variations are minor scribal errors, some are more substantial, leading to ongoing scholarly debate about the precise original wording of certain passages. [6][7] This historical reality, for Muslims, provides a corroborating context for the theological assertion of tahrif, highlighting the vulnerability of divinely revealed messages to human interference when their preservation is not divinely guaranteed in a unique manner.

Mechanisms and Evidence of Distortion

The mechanisms through which previous scriptures are believed to have been distorted are multifaceted, ranging from human fallibility to deliberate manipulation. One significant factor is the nature of transmission over centuries. Before the advent of printing, texts were copied by hand, a process prone to scribal errors, omissions, or additions. As texts were translated into different languages, further variations could be introduced. The sheer number of biblical manuscripts, while impressive in quantity, also presents a vast array of textual differences. For instance, the New Testament alone has hundreds of thousands of variants across its manuscripts. [6][8] While many are minor, some are meaningful, affecting the sense of the text. [6] Discoveries like the Dead Sea Scrolls have revealed ancient biblical texts that sometimes differ from later Masoretic texts, further illustrating the dynamic nature of scriptural transmission in antiquity. [4]

Beyond unintentional errors, Islamic theology suggests the possibility of intentional alterations. This could stem from theological disputes, political motivations, or attempts to align the text with prevailing beliefs or practices. The Quran itself points to instances where people “distort it knowingly” or “tell lies about Allah knowingly.” [3] While Western textual criticism typically avoids theological judgments, it does acknowledge that scribes and redactors sometimes made changes to texts for various reasons, including theological ones. For example, some textual critics have identified additions or changes in biblical texts that appear to reflect later theological developments or attempts to harmonize narratives. [7] The lack of a single, universally agreed-upon authoritative codification for centuries, unlike the Quran, meant that different versions and readings of biblical texts circulated, contributing to their textual fluidity. This open-ended transmission process, from an Islamic standpoint, left the earlier divine messages susceptible to human intervention, necessitating a final, uncorrupted revelation in the form of the Quran.

The Preservation of the Quran

In stark contrast to the perceived textual fluidity of previous scriptures, the Quran stands as a unique testament to meticulous preservation, a process Muslims believe was divinely ordained and humanly executed with unparalleled rigor. The preservation of the Quran relied on a dual system: robust oral transmission and immediate, widespread written documentation. From the moment revelations descended upon Prophet Muhammad over 23 years, companions committed them to memory, becoming Huffaz (memorizers). [9][10] This oral tradition was not merely individual but communal, with thousands memorizing the entire text, ensuring a living, self-correcting repository. [11][12] The Prophet himself would recite the verses, and his companions would learn them by heart, often repeating them in daily prayers. [10]

Concurrently, the revelations were immediately written down by numerous scribes on various available materials, including parchment, bones, and leaves, under the direct supervision of the Prophet. [9][11] This ensured that the entire Quran existed in written form during the Prophet’s lifetime. [12] After the Prophet’s passing, concerns arose due to the martyrdom of many Huffaz in battles. This prompted the first Caliph, Abu Bakr, to commission a comprehensive compilation of the written Quranic materials into a single volume, a task led by Zayd ibn Thabit, one of the Prophet’s principal scribes and a memorizer himself. [11][13] This initial compilation served as a master copy.

The definitive standardization occurred during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan (c. 650 CE). [14][15] As Islam expanded, variations in recitation and dialect emerged among new converts, threatening the unity of the Muslim community. [11][14] To address this, Uthman commissioned a committee, again led by Zayd ibn Thabit, to produce a standardized version based on Abu Bakr’s compilation and cross-referenced with the oral traditions of the most authoritative reciters. [14][15] This Uthmanic Codex, written in the dialect of Quraysh (the Prophet’s tribe), became the authoritative text. [11][15] Copies were meticulously made and distributed to major Islamic centers, and all other variant manuscripts were ordered to be destroyed to prevent future discord. [14][15] This decisive act, while sometimes viewed as controversial by external observers, was crucial in establishing a singular, universally accepted text. [14]

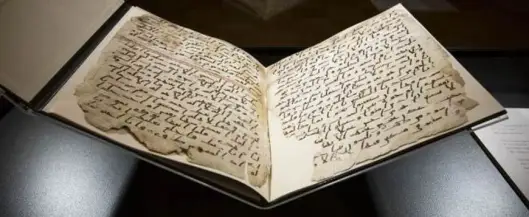

The result is a text with remarkable consistency across centuries and geographical regions. Studies of early Quranic manuscripts, such as the Sana’a manuscript, reveal a striking conformity with the current text, affirming its preservation. [9][16] While minor orthographic variants or copyist errors exist, scholars note the virtual absence of meaningful or viable variants that would alter the sense of the text, especially when compared to the textual history of the Bible. [6][17] This textual stability, coupled with the unbroken chain of oral transmission (isnad) from the Prophet’s time to the present day, provides a compelling case for the Quran’s integrity. Muslims believe this unparalleled preservation fulfills the divine promise, “Indeed, it is We who sent down the Qur’an and indeed, We will be its guardian.” [12][16]

In conclusion, the Islamic narrative presents a profound distinction between the historical trajectory of previous divine revelations and the Quran. While earlier scriptures, despite their sacred origins, are believed to have succumbed to various forms of human-induced distortion over time, the Quran stands as a testament to a unique and divinely orchestrated preservation. The rigorous methods of oral memorization and meticulous written compilation, culminating in the authoritative Uthmanic Codex, ensured the textual integrity of the Quran. This stark contrast underscores the Islamic belief that the Quran represents the final, complete, and uncorrupted word of God, safeguarded against the alterations that befell its predecessors, thereby serving as the ultimate guide for humanity.